There’s an ad campaign currently running for a large mutual fund company known to have high expense ratios within its products. I’m paraphrasing, but one of the claims goes something like this: “Long-term returns matter more than costs today.”

Depositphotos.com contributor/Depositphotos.com – MarketBeat

I sort of agree.

On the one hand, it’s better to have an investment plan, tailored to your goals, time horizon and risk tolerance, rather than winging it.

On the other hand, I’ve seen way too many people overpaying for funds, when they could easily gain exposure to the exact same asset class at a lower price.

For example, the Rydex S&P 500 C mutual fund (RYSYX) carries an expense ratio of 2.390%. That may not sound like a very high number, but that can be deceiving.

This fund’s investment strategy is pretty simple. According to manager Guggenheim, the fund “Seeks to provide investment returns that match, before fees and expenses, the daily performance of the S&P 500 Index.”

That’s hardly an unusual strategy. Tracking an index, particularly one as established and ubiquitous as the S&P 500, is the task of many a mutual fund or ETF.

In fact, the SPDR Portfolio S&P 500 ETF (NYSEARCA: SPLG), the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (NYSEARCA: VOO) and the iShares S&P 500 ETF (NYSEARCA: IVV) all do the same thing – and all for the measly expense ratio of 0.03%!

I get it. Your 401(k) may have limited choices, so you may be stuck with funds that have higher-than-average expense ratios. In that case, I’d say that investing in those is absolutely better than doing nothing. You get in the habit of salting away some money from every paycheck and you’ll still participate in market growth.

But if you are able to, why not save some money by using cheaper funds? If you are invested in an IRA, you have more control over the funds you can own. Many roboadvisors use low-cost diversified ETFs, allocated toward the account owner’s age, goals and risk tolerance.

You’re not necessarily stuck with all your funds in an expensive 401(k). Many companies allow what’s called an “in-service withdrawal” once you are 59 ½ or older. That means you can roll over some of your qualified account assets to an IRA while you are still working at the company.

This could give you access to cheaper funds and potentially an even better investment strategy overall.

If you do happen to own mutual funds, it’s important to recognize they’re not all brimming with exorbitant fees. For example, funds from Vanguard and Dimensional Fund Advisors are known for low expense ratios, and you won’t find commissioned brokers pocketing some extra cash for selling you these funds. That practice is perfectly legal for brokers who are not fiduciaries, although it’s not exactly in your best interest.

Fortunately, it’s easy to do a little research on your own, and figure out how much you are actually paying.

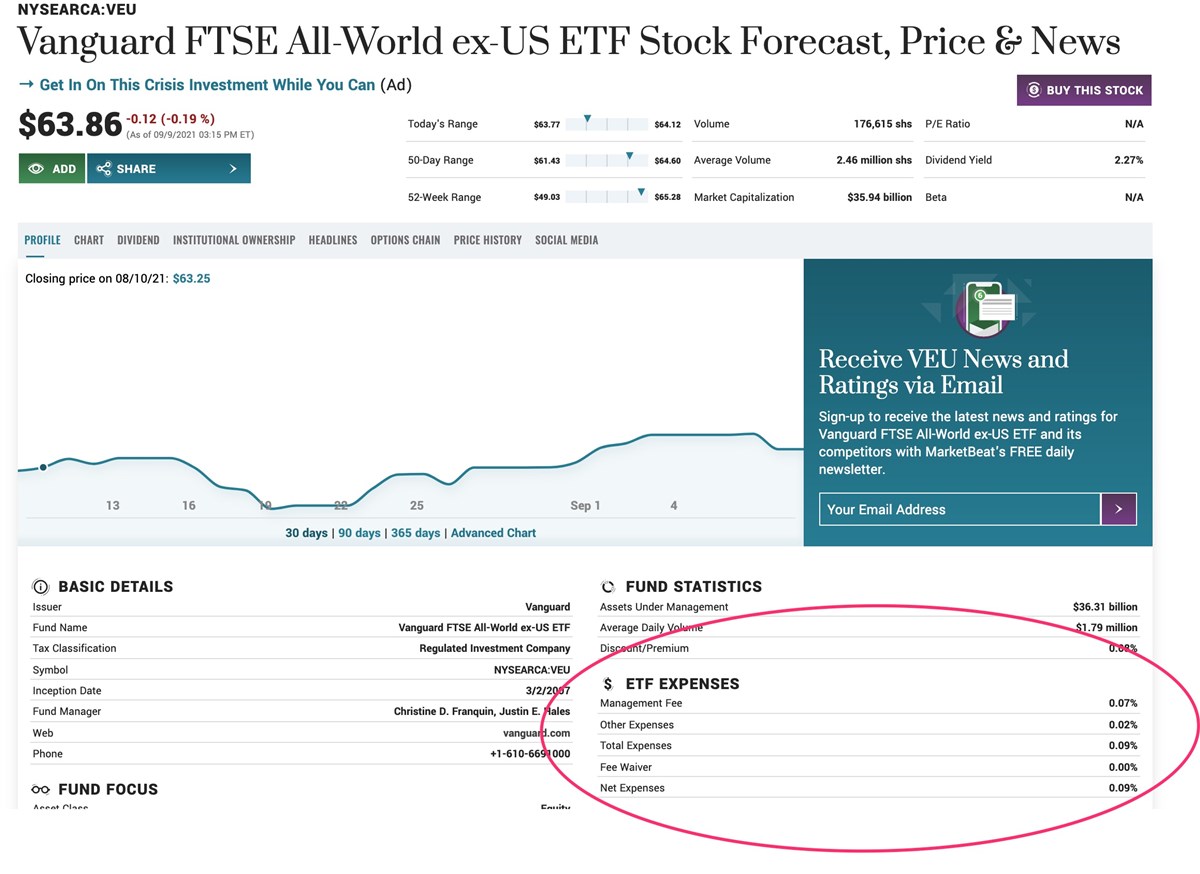

When it comes to ETFs, MarketBeat provides data on expense ratios. For example, here’s the Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US ETF (NYSEARCA: VEU). Scroll down to the section titled ETF expenses, and you’ll see exactly what you’re paying. This is an example of a very low-cost fund, to put it in context.

However, with mutual funds, here are some of the charges you may find:

Management fees. This is a fee collected by the fund management company. It’s never free to run a fund, so it’s fine that fund managers charge something. Generally, funds that track an established index charge lower fees than active funds, or even those tracking a custom index. I once had a client ask me whether a higher fee meant better performance. Unfortunately, a manager can’t guarantee performance, so there’s no mechanism to charge a higher fee with that expectation in mind. In addition, the fee may actually cut into your performance, rather than reward a manager for superior stock picking.

12b-1 fees. This is just a fancy term for a commission. It’s where that stock broker gets paid for investing your money in a particular company’s fund. If you work with a fee-only registered investment advisor, he or she cannot, by law, charge these fees. Make sure you understand exactly how your advisor’s business is structured.

Redemption fees. Funds are allowed to charge a fee to investors who choose to sell shares. This doesn’t generally extend to the entire time you hold a fund, but it can apply to sales with a specified time period, such as 30 days or even a year. The idea is to keep your assets invested, which is generally a good idea, but you don’t want to needlessly fork over money to some fund manager if you need to cash out for some reason.

Load. Even the name is ugly. This is a sales charge that goes to a sales person (a commissioned stock broker) for selling you a particular fund.

As you see, there is plenty of potential for these fees to add up. If you work with an advisor, be certain you understand whether he or she operates as a fiduciary at all times. If you handle your own fund investments, do a little research to determine whether you can own the same asset classes at a dramatically lower cost.